I am attempting to gradually visit all of Amsterdam’s museums in roughly alphabetical order. The previous one was the Heineken Experience. The next one is Het Glazen Huis.

The Amsterdam Hermitage is a museum that is something of a sister of the St. Petersburg Hermitage, which is amongst the largest museums in the world. It has temporary exhibitions from all over, presenting the collections of other museums here in Amsterdam and abroad.

This does mean that what I’m saying here may be different for you when you visit.

The Hermitage when I went (late August/early September 2017) had three exhibitions, which I’ll detail separately. There’ll be a lot of photos. Due to difficult lighting, some of them are a bit glary. Sorry about that.

Entering the Hermitage, you start in a really nice courtyard.

The building was once a home for elderly women, able to house 400 of them. By 2007, the building was considered no longer suitable for its residential care purpose, and the last of the residents were moved out. From then it was rebuilt into a museum, and in 2009 it opened as the Hermitage.

Enter, collect your audio-guide, and proceed to the first exhibition. While transitioning between the exhibitions, you may get lost. That’s OK, the building has lots of interesting little rooms that are open for you to explore and it is worth seeing for its own sake.

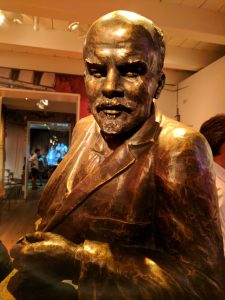

1917. Romanovs & Revolution

The End of Monarchy

Closes 17th September

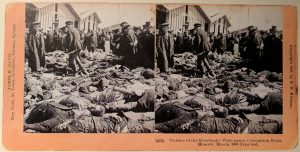

Note: there are a pair of photos in this section that show pictures of dead bodies. If you’re squeamish about that, beware.

This post isn’t going to be a complete history lesson, there are books for that, however it’ll tell a sampling of the story the Hermitage presents. The Romanovs had a long history of ruling Russia, over three centuries. This came to an end in 1917 with the Russian revolution, and a violent overthrow of the monarchy, caused by a few factors; among them the war with Germany and resource shortage in Russia.

The exhibition primarily covers the period of Tsar Nicolas II, and his fall to the Bolsheviks. There is an explicit theme throughout the whole story as presented. That is, the mistakes and failures made by Nicolas that ultimately lead to the fall of the Russian monarchy.

Initially it takes you down a corridor done like a mall.

Every half-hour it plays the sights and sounds as though it were St. Petersburg of the early 20th century

This lulls you into the false sense of security that this is going to be a short bit of history and then you can get on to the next exhibition. This is an illusion. It takes you through a quick timeline of the Romanovs, particularly Nicolas, showing you items from the time and things that were popular with the people. It will tell you about St. Petersburg.

Statuettes showing some the various ethnic groups of Russia (which was expanding at 50,000km² per year at the time.) Nicolas received two for each birthday.

It will also tell you about the history of Russia. I didn’t even know that they had a war with Japan in 1904/05. Russia lost, badly.

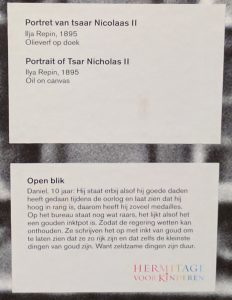

The corridor finishes with a large portrait of Nicolas.

Daniel, 10 years old: He looks as though he did good deeds during the war and shows that he is of high rank, because of this he has so many medals.

[Translate the rest yourself.]

As a bit of an aside, there’s something interesting I noticed they’re doing. Alongside the caption cards, they often have input from children talking about it. That’s pretty cool. The Hermitage has a special art education programme for children, I imagine that this is part of that.

Once you reach this end, there’s a small, innocent looking doorway. Beyond here is where the real stuff starts. The mall-like section gives you a foundational timeline of the particular period of Russian history. After this, it starts again, repeating the same timeline, but now with a particular focus on the lives of the subjects: Nicolas, his wife Alexandra, and their children Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei.

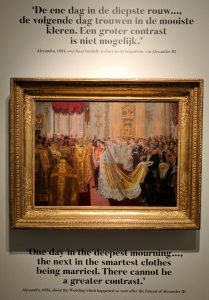

It starts at the beginning, with the marriage of Nicolas and Alexandra immediately following the death of of Nicolas’s father, Alexander III, in 1894. A couple of years later there was the coronation.

Many people died in the coronation, as presents being distributed turned into a stampede. Despite this, the Tsar and Tsarina went to a ball that evening (under some duress, apparently.) This was considered a bad thing to do and made people a bit grumpy, leading to him being called “Nicolas the Bloody.” This event was the Khodynka Tragedy, and nearly 1,400 people were killed.

Time went on, and people grew less and less happy with his rule, and were starting to show it. There were protests, government soldiers shooting people, and Nicolas responding by retreating into private life, which in turn caused people to be less happy with him still.

Photos of the children, and some of their stuff. Alexei was haemophiliac and always unwell, hence his rather depressing quote there. (click this for a higher-res version.)

Soon the Tsar abdicated with no successor, the Russian revolution kicked off, and the family was evacuated from Moscow due to fears over their safety. They were placed under effective house-arrest in the Urals. During their time there Lenin gained in power, and there was talk of putting them on trial.

At this point, there was fear of the Germans invading St. Petersburg, and so much of the original Hermitage collection was moved to Moscow for safety. Empty frames illustrate this.

Eventually, the Bolsheviks start to execute anyone associated with the monarchy, including extended family. Nicolas and his family are told that they are going to be moved, perhaps to exile elsewhere. Instead, they are executed.

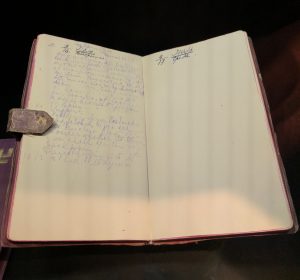

The last diary entry of Alexandra. It details the weather (grey morning, sunny later), that they had supper, and they went to bed at 10:30. It was 15 degrees.

A bayonet used to kill the imperial family. Due to having jewels sewn into their corsets, the girls were bulletproof, so this was used instead.

This is a particularly interesting exhibition of a turbulent time in history that went on to change the entire world. Be aware that it took me nearly two hours to get through, and so I’d suggest you start early, especially if you want to see the other parts of the Hermitage also.

Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age (Hollanders van de Gouden Eeuw)

An extremely classic form of Dutch art is the portrait, often very large. Back in the Golden Age, 1600-1800 or so, Amsterdam wasn’t run by Kings and Queens so much as by the wealthy elite of business. One of the things they did in order to show their status, wealth, and to be recognised was to commission portraits. As is the case in Rembrandt’s classic The Night Watch, these were often groups showing the important organisations that the people were members of. It was considered the duty of every citizen who could afford to buy the equipment to be a member of a civic guard, and people in these groups often held a not insignificant amount of influence.

This exhibition takes collections from the Rijksmuseum and the Amsterdam Museum and presents them for the first time together. It tells the story of the people who built Amsterdam into one of the most powerful trading cities of Europe at the time.

The civic guard of 1650, these are the people who keep order in the city, both from internal and external problems. This was also too large to fit in my camera.

This exhibition uses light and animation to very good effect. In a few places, it highlights individuals by lighting them up and telling you about them specifically. Unfortunately these effects don’t photograph well, but they look very good in person.

The second of the two photos above is from the large gallery room. Every 15 minutes in there they turn the lights down, and in a few areas light up people and tell you about them via the audiotour system. This repeats, giving you enough time to get to all the parts. It’s really very well done. The gallery itself is very impressive.

As is a theme in this museum, you get to the end of a room like this and think that it must be the end. Then you spy a small doorway, follow it, and realise that you barely got started.

The centre of this is the earliest known civic guard portrait, from 1529. The wings were added around 1559.

Members of the Amsterdam Calivermen’s guild, ready for battle. Note the fantasy landscape in the background showing “mountains.” Like they even exist anywhere.

Lest you think that this is only about people, it has some interesting images of the cities of the Holland region. I particularly like the ones showing the city walls, which no longer exist.

Amsterdam’s Dam Square from 1675. Town hall on the left, and tourists (you can tell, they wear turbans) gazing in awe. Much like these days.

Public transport, between Amsterdam and Haarlem. This is the view of a gate into Amsterdam from Haarlemmerpoort. About 5 minutes bike from where I live. Vergeet u straks niet uit te checken.

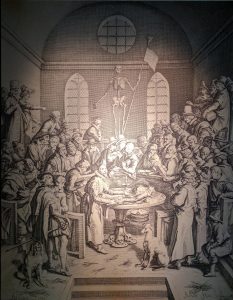

Another section of interest is the anatomy lesson collection. In a nutshell, the presentation of anatomy was a common public spectacle in winter times. The bodies were typically sourced from convicted criminals.

Finally, they tell us that the art of portraiture is not dead.

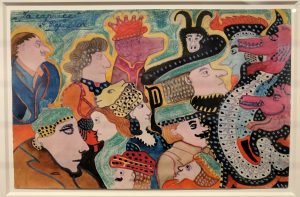

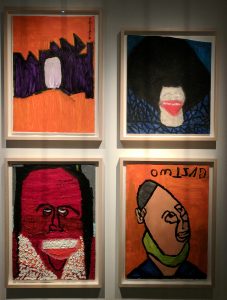

Outside Art Museum

This final section is a great departure from the previous one. It contains art from artists outside the mainstream, often not discovered until after their deaths. As a particular example, many of the items are art created by psychiatric patients.

As a recognised form, this started after World War 2, with psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn. This was later added to by the French artist Jean Dubuffet in 1972, with Art Brut.

Unfortunately due to the lighting in this area, photos didn’t really come out well. In addition, this is a very hard exhibition to provide context on through writing. The best way is to see it for yourself. As such, this section is very short.

Practical Details

- Cost: It’s complicated. A combination ticket to see all exhibitions is €25 for adults, or €2.50 with a Museumkaart. There are other discounts too, or maybe you only want to see one or two things. Check the website.

- Language: All signs are in Dutch and English. The audiotour is multilingual though there is some extra stuff in Dutch only in parts.

- Location: Amstel 51, near the Waterlooplein stop. Metro or tram will get you there. Or you can probably walk it from wherever you happen to be, it’s very central.

- Hours: 10:00 to 17:00. Be early as it’ll take you longer than you think to get through everything. Trust me on that.

where is this? can i go there?

i hope oneday i can go there. nice articles, keep on writing 🙂